Albanese Battles Political Storms Ahead of May Election

Cyclone Alfred slammed into Australia’s east coast this month—and with it, derailed the Prime Minister’s expected election timeline.Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was ready to ride a wave of positive economic news—particularly a rare reprieve in interest rates—to announce an April election. But then Cyclone Alfred hit, forcing a sudden pivot from campaigning to crisis management. One Labor minister described it bluntly: “It was an act of God.”

That moment, in many ways, encapsulates the challenges Albanese’s government has faced: grand plans repeatedly knocked off course by global turmoil, rising living costs, international conflicts, post-pandemic instability—and now, natural disasters.

“Global conditions are real,” Albanese said as he officially confirmed a 3 May election date.

Still, he insists Labor has delivered despite the headwinds. Citing falling inflation and rising wages, he likened the government’s economic management to “landing a 747 on a helicopter pad.” Now, he’s asking voters for a second term to reset and go further.

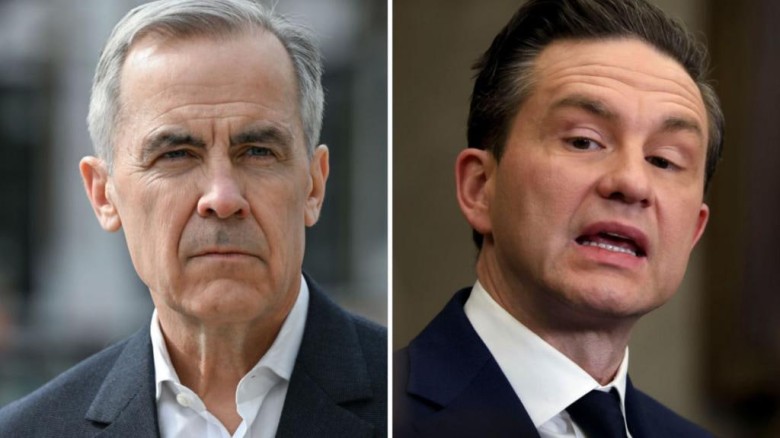

Standing in his way is Peter Dutton, the conservative Liberal Party leader and head of the Coalition alongside the Nationals. Just two years ago, polls had Dutton trailing in popularity. But fast forward to today and the race is neck and neck—tight enough that many expect a hung parliament, with independents and minor parties potentially holding the balance of power.

From a Fresh Start to Frustration

Albanese swept into power in May 2022, promising a new era after nearly a decade of conservative leadership. Climate action, cost-of-living relief, and stable governance topped the agenda.

But his defining ambition lay in Indigenous reconciliation. He had pledged a referendum to establish an Indigenous Voice to Parliament—an advisory body meant to represent First Nations people on issues affecting their communities. His government spent most of 2023 campaigning for a "Yes" vote.

Instead, the proposal was rejected by a significant margin. Around 60% of Australians voted "No," leaving many Indigenous Australians hurt and disillusioned—and Albanese politically bruised. Critics pointed to misinformation and public confusion, while Dutton used the moment to accuse Albanese of prioritising a costly referendum over day-to-day economic struggles.

“[Dutton] not only won on the referendum,” said former Labor strategist Kos Samaras, “he also succeeded in painting Labor as distracted from what really matters.”

The Economy, the Cost-of-Living Crisis, and Blame

Since Albanese took office, Australia has endured 12 interest rate hikes (with just one cut in February), soaring inflation, and a worsening housing crisis. While the Prime Minister often lays blame at the feet of the previous Coalition government, voters are increasingly focused on who can tackle the issues now.

In his 2022 victory speech, Albanese called Australia "the greatest country on earth." But with growing frustration over housing, prices, and stagnant wages, many voters are starting to question that claim—and whether either major party has the answers.

And while discontent with Labor is real, that doesn’t automatically translate into votes for the Coalition. At the last election, support for independents and minor parties hit record levels, and it’s expected to remain high. If neither major party can win the 76 seats needed for a majority in the House of Representatives, independents could decide the next government.

That would echo a broader global trend: a growing wave of voters rejecting traditional parties in search of more radical or independent alternatives. In many parts of the world, that shift has shaken democracies. But Australia’s electoral system offers some safeguards against extreme swings.

Why Australia's Democracy Holds Steady

Australia’s compulsory voting system ensures high participation. In 2022, nearly 90% of eligible voters cast a ballot—far above the OECD average of 69%. That makes election results more representative, and reduces the impact of fringe groups dominating the narrative.

Preferential voting also plays a stabilising role. Instead of voting for a single candidate, Australians rank them in order of preference. This system has helped newer parties like the Greens and One Nation gain ground, while still anchoring the political centre around Labor and the Coalition. It forces the major parties to appeal to a wider voter base—even those who might not support them as a first choice.

“Elections here are decided in the middle,” says Australia’s chief election analyst Antony Green. “It’s about reaching people who aren’t paying much attention.”

The Global Factor

While domestic issues dominate the campaign, international politics looms large. A potential return of Donald Trump to the White House is already raising concerns in Canberra. Five months ago, few believed a Trump presidency would significantly affect Australia—but now, it’s on voters’ minds.

Trump’s unpredictable stance on alliances and trade adds to anxiety about Australia’s role in the global order. Dutton claims he would manage Trump better than Albanese—but in truth, no one seems confident in how to handle a potential second Trump administration.

With the campaign officially underway, voters now have just over a month to decide who they trust to lead them through an increasingly uncertain future.

Albanese's response to Cyclone Alfred may have boosted his approval ratings to an 18-month high, but the polls suggest Dutton is still within striking distance. For Labor, the risk of becoming the first one-term government since 1931 is very real.

Leave A Comment