Reagan-Era Republicans Condemn Trump’s Russia Policy Shift

Veterans of the Reagan Administration Express Disbelief at Trump’s Foreign Policy Stance

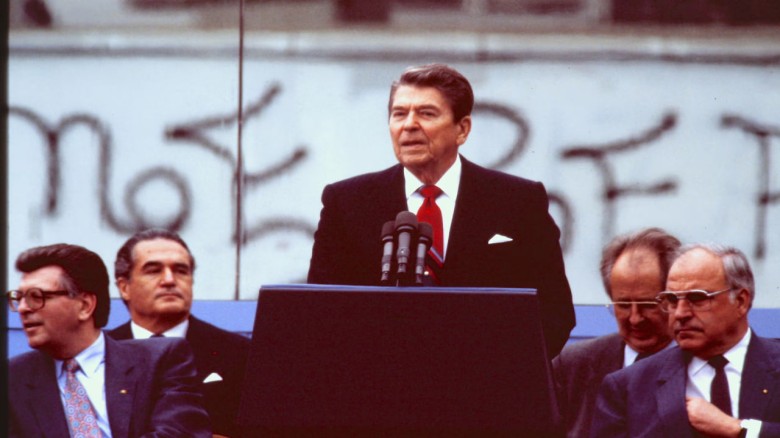

Prominent Republicans who served under President Ronald Reagan during the Cold War have voiced their dismay over Donald Trump’s approach to Russia and his apparent disregard for the longstanding transatlantic alliance.

European leaders were left stunned last week after U.S. Vice President JD Vance declared at the Munich Security Conference that Europe’s greatest challenge was “the threat from within” rather than external dangers. His remarks, which suggested a retreat from shared democratic values, have intensified concerns about the direction of U.S. foreign policy.

Adding to these worries, a high-level meeting between American and Russian diplomats is set to take place in Saudi Arabia, conspicuously excluding Ukrainian and European officials. Critics fear this signals a potential concession to Moscow. “It makes me sick to see what’s happening,” said Ken Adelman, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. “The Trump administration has no respect for 80 years of Atlantic cooperation or Ukraine’s sovereignty.”

Adelman, who served as Reagan’s arms control director and was present at three historic summits with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, contrasted the past and present approaches to Russia. “Reagan told Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall. Trump is telling Putin to do whatever he wants. Reagan stood by allies and challenged adversaries, whereas Trump seems to do the opposite.”

For decades, staunch anti-communism defined the Republican Party, culminating in the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. U.S. military presence in Europe has long been a stabilizing force for democracy. However, since launching his political career, Trump has aligned with nationalist-populist ideologies and shown a reluctance to criticize Russian President Vladimir Putin. Many within the Republican Party have followed suit, while Reagan-era conservatives such as Mike Pence, Liz Cheney, and Adam Kinzinger have been sidelined.

Adelman lamented this shift: “I’m astonished that the Republican Party has abandoned principles it held for decades in favor of an ‘America First’ stance that history already discredited by 1942.” He remains hopeful that reason will prevail, saying, “There’s still a chance for Republicans to ask themselves what they truly stand for.”

Trump’s second term has seen an increasingly unrestrained approach to foreign policy. Whereas his first term featured officials like Vice President Mike Pence and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis attempting to maintain transatlantic ties, the current administration—represented by Vance and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth—has taken a more confrontational stance.

Vance’s comments in Munich, which accused European leaders of mishandling immigration, suppressing free speech, and ignoring their voters, were met with strong pushback, particularly in Germany. He also criticized mainstream German parties for their refusal to collaborate with the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), a stance that was sharply rebuffed by Berlin.

Leon Panetta, former Defense Secretary and CIA Director, criticized Vance’s rhetoric: “The U.S. and Europe fought a world war to ensure Nazism never again dominated the continent. For him to suggest Germany should ignore that lesson is neither smart nor constructive. We need to strengthen alliances, not disrupt them.”

Panetta, a Democrat who served under Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, acknowledged the Republican silence on these issues, stating: “The GOP was once the party of strong national security. Now, they seem to have chosen to stay silent and fall in line. That’s not what they were elected to do.”

Vance also cast doubt on continued support for Ukraine, hinting that European nations might be excluded from future negotiations. His emphasis on America’s differences with Europe rather than shared values left diplomats concerned about a growing rift.

John Bolton, former national security adviser to Trump, remarked, “It seems like they deliberately set out to shock the Europeans. The Trump administration has a pattern of publicly undermining allies while sparing Russia and China from similar treatment. That might have worked in real estate, but it carries serious consequences for U.S. foreign policy.”

Further complicating relations, Hegseth declared during a NATO meeting that the U.S. would not support Ukraine’s NATO membership and called Kyiv’s demand for a return to its pre-2014 borders “unrealistic.” Senator Roger Wicker, chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, dismissed Hegseth’s remarks as a “rookie mistake,” telling Politico, “I don’t know who wrote that speech, but it sounded like something Tucker Carlson would say. And Carlson is a fool.”

Wicker’s rare Republican critique suggested that dissent exists within the party, though many lawmakers remain wary of openly opposing Trump. Bolton added, “The good news is that most Republicans in Congress don’t want Russia to gain an upper hand. The bad news is they’re too afraid to say so publicly.”

Concerned by the escalating tensions, France convened an emergency European summit in Paris following the Munich conference. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has made it clear that Kyiv will not accept a deal negotiated behind its back. Yet, at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago, Trump appeared to blame Ukraine for prolonging the war—another move that fractured Western unity.

Bill Kristol, director of Defending Democracy Together and a former official in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations, expressed his concerns via email: “Reagan would have emphasized that NATO and U.S. commitment to Europe have ensured peace for 80 years. Undermining that alliance is reckless. And for what? To appease Putin?”

As Trump’s second term unfolds, the Republican Party faces a defining moment: will it continue shifting toward isolationism, or will it reclaim the global leadership and steadfast alliances that once defined it?

Leave A Comment