Stubble Burning Surges in Punjab Amid Changing Farm Practices and Shrinking Cattle Population

Punjab, May 30 — Wheat residue burning has once again surged across Punjab, with over 9,900 reported cases of stubble fires this season as of May 24—92% of which occurred in May alone. The practice, long criticized for its environmental impact, is being driven by changing agricultural dynamics, a shrinking milch cattle population, and rising input costs, say experts and farmers alike.

As farmers prepare fields for transplanting paddy saplings between May and June, burning leftover wheat stubble has become a widespread and cost-effective method of clearing fields. “Managing fields through institutional methods costs over ₹1,000 just in diesel,” said a farmer from Fagan Majra village. “Burning is far cheaper—it only takes a matchstick.”

The declining utility of wheat straw is a key factor behind the growing trend. Official livestock census data reveals a drop of 2.32 lakh cattle and 5.22 lakh buffaloes compared to 2019, leading to reduced demand for wheat straw as fodder. Meanwhile, industries that previously used wheat straw as fuel have shifted to paddy bales, further diminishing its economic value.

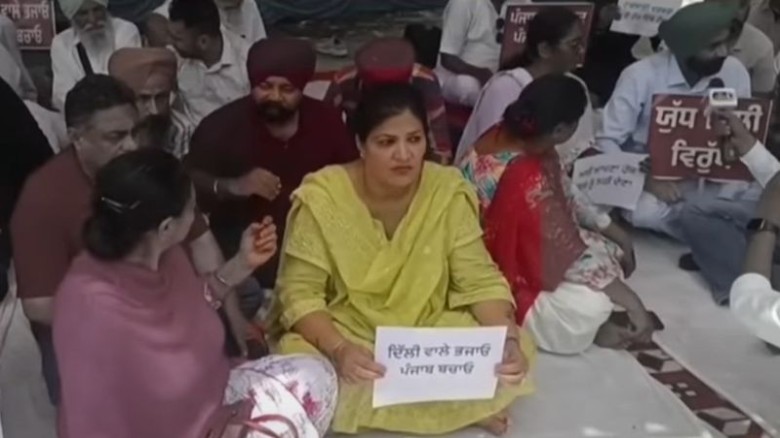

The Punjab Pollution Control Board (PPCB) has been criticized for its silence on the issue, while field reports indicate that stubble is being burned during the scorching afternoon heat and nighttime hours. The practice persists despite legal prohibitions and health risks from air pollution.

Farmers defend stubble burning not just on economic grounds but also for agronomic reasons. They argue that wheat stubble blocks sunlight and hinders the growth of transplanted paddy saplings if left in the field. A common refrain is: “Parali zameen ch khilri changi nahi lagdi” (Stubble doesn’t look good on ploughed land).

However, agronomists challenge this notion. “There’s no scientific basis for the belief that wheat residue harms paddy crops,” said Dr Hari Ram, Principal Agronomist (Wheat) at Punjab Agricultural University (PAU). “Incorporating the residue into the soil actually improves fertility and reduces the need for chemical fertilisers.”

The practice of puddling—tilling the field while it’s flooded for paddy transplantation—complicates residue management. Floating stubble can interfere with saplings, forcing farmers to manually remove it, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive.

PAU Vice-Chancellor Dr Satbir Singh Gosal stressed that the root of the problem lies in a demographic and cultural shift in rural Punjab. With youth migrating in large numbers and cattle rearing in decline, farmers have fewer reasons to retain wheat straw. “Burning has become a quick fix, but it severely damages soil health by depleting nutrients,” he warned. “Farmers must shift to sustainable practices like in-situ residue management to avoid over-reliance on synthetic fertilisers.”

While some advocate for Direct Seeding of Rice (DSR) as a potential solution, experts caution it is only suitable for specific soil types and paddy varieties. Dr Jagrup Singh Sidhu recommends aligning paddy sowing with the monsoon by extending the interval between harvest and planting, and adopting heat-tolerant wheat varieties to improve field management.

Interestingly, older generations in Punjab used wheat straw more resourcefully, mixing it with mud to make water-resistant coatings for rooftops—a stark contrast to its current status as an agricultural by-product destined for burning.

As Punjab battles recurring farm fires, the situation calls for urgent policy interventions, increased awareness, and technological support to help farmers transition toward more sustainable methods.

Leave A Comment